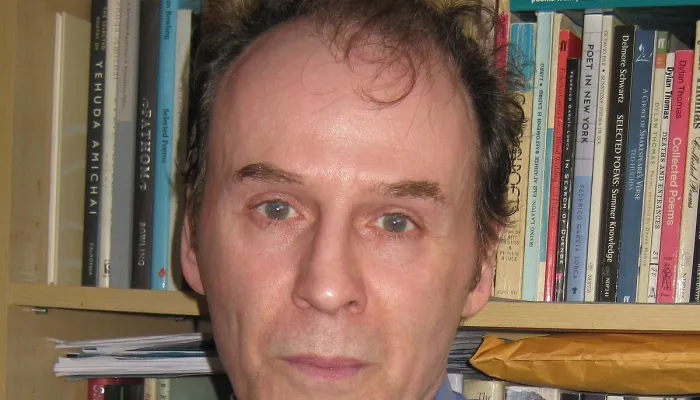

Adam Sol

Biography

Born in New York, Adam Sol has lived in Toronto for 25 years. He has published five books of poetry, including Broken Dawn Blessings, his most recent collection, which won the Vine Award for Canadian Jewish Poetry. His novel-in-verse Jeremiah, Ohio was shortlisted for Ontario’s Trillium Award for Poetry and his collection Crowd of Sounds won the award in 2004. He also is the author of How a Poem Moves: A Field Guide to Readers of Poetry, a series of essays that was published in book form by ECW in 2019. The blog continues at: https://howapoemmoves.wordpress.com. He teaches at the University of Toronto's Victoria College, where he holds the Blake C. Goldring Professorship and is Coordinator of the Creativity & Society program.

His poetic interests circle around the complications of being a person, how we are at once serious human beings with spiritual yearnings and socio-political frustrations, and also people who like to play stupid video games and eat beaver tails. How can poems reconcile these conflicting selves? He went to school for a long time and earned a bunch of degrees, but gets equal inspiration from the goofy as the esoteric, from Herman Melville to Bert & Ernie, from Talmudic stories to the Toronto Raptors.

Micro-interview

I didn’t like my high school English teacher much. He didn’t seem to enjoy us, or his work. But we had a big thick textbook with a lot of stuff in it that I liked to leaf through. One day when Mr. Gambini was nattering on about something, I happened upon a poem by Randall Jarrell, “The Death of a Ball Turret Gunner.” It ends with the brutal line: ”When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.” I had no idea that poems could be so tough and gross and poignant all at the same time. My 14-year-old self was hooked. Could I do things like this?

I remember writing a poem when I was about 8 years old protesting the fact that the local fairgrounds was being torn down so that they could build a mall. “They tore down the fair and they’re putting up a mall. / Sometimes I wonder if they think of us at all.” Something about how kids couldn’t vote on the decision. It was a Poem of Civic Protest. Years later I’d sling pizza at that mall, and write poems about my Ecuadorian co-workers, who taught me how to swear in Spanish.

I started trying to take poetry seriously in grade 11 or so. There was an arts program in my high school that linked us up with local professionals. I did a unit in music with a terrific percussionist, and I did a couple of units with local poets, including one who treated me with a lot of patience and respect and made me feel like I was onto something. That was encouraging, and gave me an inkling that I wanted to try more, so that when I went to university I was ready to dive in.

This is a good one. My simple glib answer is, “To speak to the people.” But that just opens up lots more questions: Which people? Speak how? Say what? To me, all of those questions can be answered in different ways. Some poets speak to a wide range of people delivering messages that try to motivate them to action or change their way of thinking on a subject. Some poets speak to a narrower group of people trying to express something essential about what it is to be human. Some poets speak to a highly specialized group of literary people and try to push the boundaries of what art can do. There are poets who share aspects of all three of these types, and I’m sure I’m missing some other categories. But all of them share an ambition to speak to readers in ways that engage and challenge them. No one wants to be a poet who says the same old thing, but all of us want others to feel spoken to in a real way.

[“Opus 75, Sestina in B-flat for the Glockenspiel”] started in a classroom, one that I was teaching. The sestina is one of those complicated poetic forms that makes some readers roll their eyes with impatience, but I like something about how the repeated words force us to examine and re-examine a subject. Sort of like turning a crystal geode around and around, looking for the best place to strike and crack it open. I also find that it’s good to use some end words that are very flexible (like “practice” or “play,” both of which can be nouns or verbs or even adjectives) and other words that are very inflexible, that anchor the poem in a certain way. So I was teaching about the form, and asked for suggestions of a concrete noun that we could use in a classroom exercise, and a smart-alecky student named Jonathan Eskedjian suggested “glockenspiel.” Everyone laughed and we wrote some pretty horrible poems in class, trying out the form. But the challenge stuck with me, and I went home and started working.

I haven’t seen everything in the anthology, but I’m going to cheat and give two answers. The first I’d choose is something contemporary, something by a living poet, preferably someone who lives nearby. There’s something special about memorizing a poem by someone whom you could meet someday, someone who you can almost feel whispering in your ear while you read the poem. It’s an odd way to get to know someone but, like learning to play a song on the guitar, it’s a great way to get inside how a poem works, how it turns and uses language. So maybe something like “Tractor,” by Karen Solie, or Dave McGimpsey’s “71. Song for a Silent Treatment.”

Then I’d choose something much older, essentially for the same reasons, but also for the pleasure of learning something in a traditional form. Maybe John Donne or Emily Dickinson or one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. When we read poems like that on the page, sometimes our distance from the style can keep the poem at arm’s length. But when we bring it into us, memorizing it, we often find that the language and the sentiments are closer to ourselves than at first appeared. “Sonnet XVIII: Shall I Compare Thee to Summer’s Day” works that way — in the end it’s just the poet’s way of trying to say nice things about his love, but also winking about how his poem will help her stay that way forever.